|

Trax3 3.1.0

trax track library

|

|

Trax3 3.1.0

trax track library

|

Curves are separate objects in trax. They can be created as objects, using a trax::Factory; furthermore each Curve supplies several Create - methods to specify its characteristic. Each curve type might have its very special characteristic that is summarized in its CurveType::Data structure. After having properly created a curve, it can get attached to a track and such will make up the track's geometry. There also exist trax::CreateCurve methods that help to create the best fitting curve for solving a special geometrical problem. These also are used by the trax::Strech methods, which directly change a track and might be more convenient to use if you are writing a track editor.

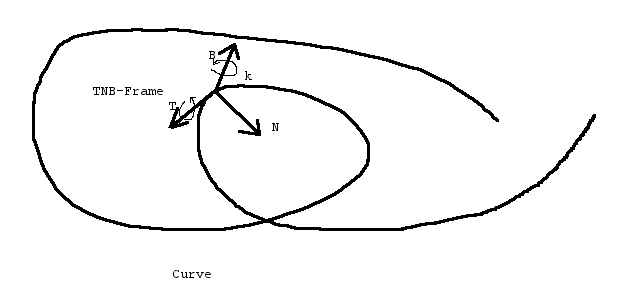

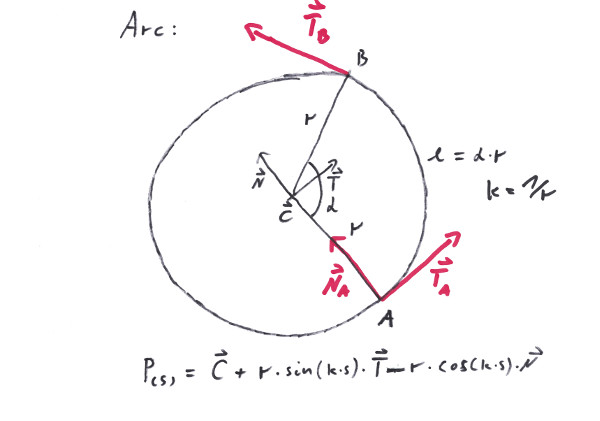

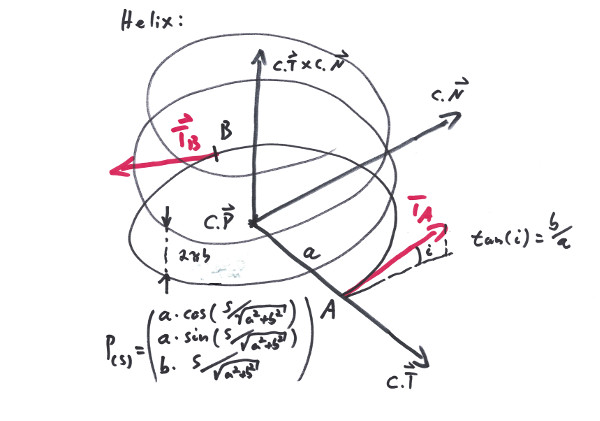

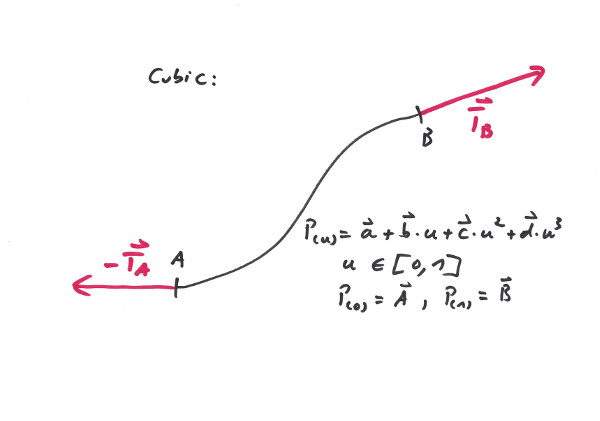

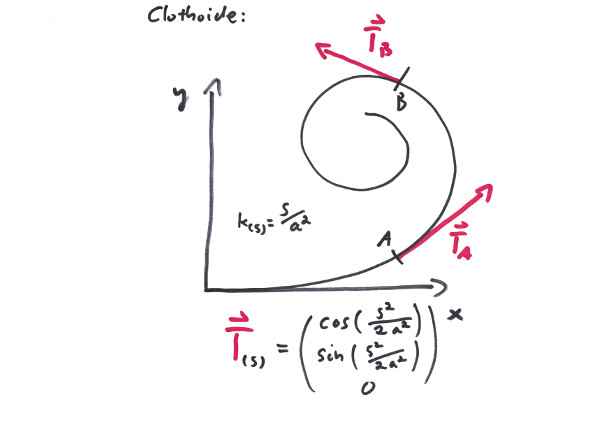

A Curve describes a path in space. That path alone determines a tangent vector T that is directed parallel to the curve at every point of it. A second vector N, the normal vector, is pointing in the direction of the mean curvature and it happens to be orthogonal to T. From that, the binormal vector B = T x N can get constructed. Now: two french guys, monsieur Frenet and monsieur Serret, some 160 years ago figured out that this TNB Frame construct is moving with the parameter value along the curve in a predictable manner, maintaining its orthogonality and relationship to curvature and torsion of the curve.

Since trax is build to work with ODE or PhysX style physics engines, and these engines happen to deal with velocities (linear and angular) rather than with positions and orientations, we can not ignore those facts about our TNB frame (well, we tried, but didn't work).

Unless differently stated, all curves are parameterized by their arc lengthes. To work with the physics engine, this is a requirement. Even if no physics engine in the strong sense is applied it is required to get physically meaningfull values for the track paramer. You might want to move a position along the track by ds = v*dt with v being a velocity; this can only work with Curves parametreized by arc length.

Just with the Curve alone there is no such thing defined as an upside or up direction of the Curve in every point. One might be tempted to mistake the binary vector B for that, but this is plain wrong. Believe us, we tried: in general that vector, like the whole frame will happily rotate around T in all so fancy ways. Since this is often not acceptable for tracks, which typically maintain strong ideas about what is supposed to be 'up', we provide a trax::RoadwayTwist for fixing that. Curve and twist define the inner geometry of a track.

A single Curve can be shared with several tracks. So some standardized tracks could be created the same way like it is done in model railroading.

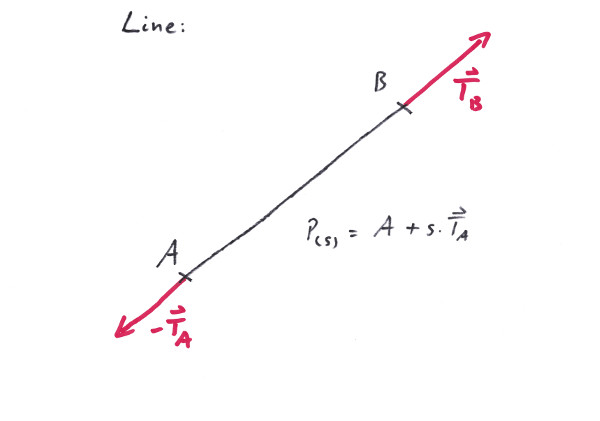

A Line is the shortest curve that connects two arbitrary points in space. Albeit this is a very powerfull feature, it might turn out to be a little bit cumbersome on the edges as well as in the middle.

When Giotto was asked by the Pope for a sample of his artisanship, he drew a perfect Arc - freehand. The Arc is regarded by many people as the most beautiful of all curves; others worship it because of its capability to avoid obstacles by circumventing them. The Arc is very well able to connect two points, even while maintaining one of the tangents, but the second tangent then would be given - all beauty suffers from limited flexibility. Since the Arc is a plane curve, it performes very poorly when dealing with three dimensions.

The Helix is the first choice when it comes to climbing from one level to another, or - when tilted - to build a looping. It can connect two nearly arbitrarily situated points and albeit it is a little bit restrictive with its tangents, a full loop has two parallel tangents at the ends - a feature that in many situations comes in handy.

The Cubic is a most powerful curve, when it comes to connecting two points and maintaining both tangents. With railways this is an important feature if it comes to close a gap or make a clean change in level, since it can work in all three dimensions. On top of this there exist two parameters that allow to further fine tune the exact path of the curve. On the other hand, since the Cubic maintains very wild ideas about its up direction it is essential to use it in conjunction with a directional twist.

The Clothoid is a curve with linearly (with respect to its arc length) varying curvature. This is a most usefull feature in traffic systems, when it comes to smoothly transition between curves of different curvature. Since it happens to be a plane curve, it is somewhat inflexible if it has to deal with more then two dimensions.

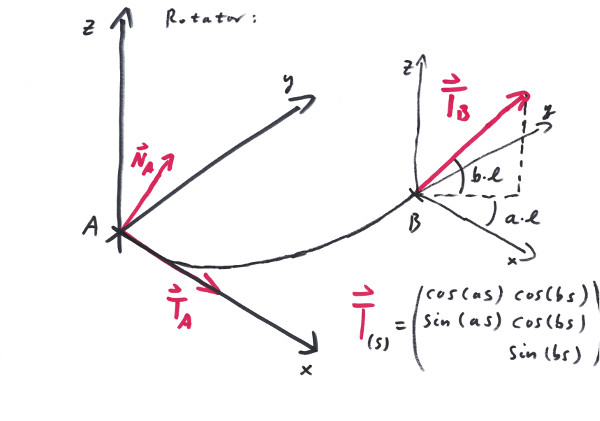

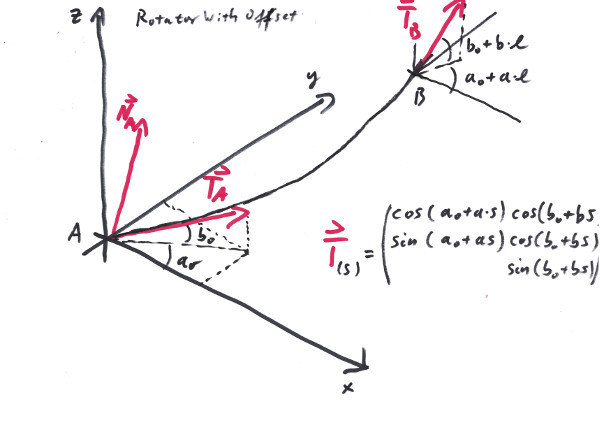

The Rotator is a curve that constantly rotates (with respect to its arc length) in the plane and perpendicular to it. Its strong side is the ability to determine the direction of the start and end tangents as well as its simplicity of concept. It works in a predictable manner especially if the rotation into the up direction stays reasonably small. On the other hand it can be a very cumbersome curve if used for tasks that it aint made for.

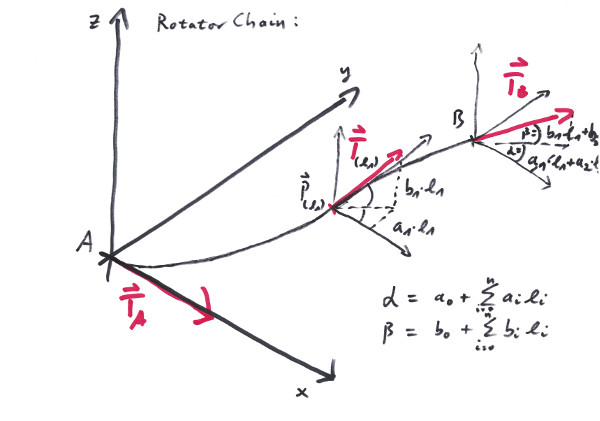

The Rotator raises the question, wether Rotators can be appended to each other, so that the total rotating angles add up in a straightforeward manner. Unfortunately in general the answere is: no. The RotatorChain cures that, since it defines a series of Rotators with respect to the same rotational axes.

To create a quarter circle, starting from origin:

To use one of the helper functions, to create the same Arc:

To create a Cubic, connecting two points, but starting and ending with parallel tangents:

Do also look at the tests in the test suit for further examples.